In addition to celebrating the end of each year and the start of a new one, we also at this time of year sadly reflect on the number of lives lost on our roads. The road toll climbs higher almost every year. Are we getting worse as drivers? Are we speeding more, or are we more distracted? Authorities have used these as reason to impose increasingly heavy fines for even minor transgressions.

There’s another side to the statistics that’s worth thinking

about. Now, before anyone channels their inner Greta Thunberg with a “how dare

you!” for raising this, I’ve lost two good friends due to road fatalities – one

of whom was my best mate. I was first to find him, and with another mate we did

our best with CPR and mouth to mouth. Unsuccessfully as it turned out, to my

eternal regret. I hope others never have to experience that. So by looking at

the data I am acutely aware that the numbers represent the lives of people and the hurt of those left behind.

But the facts matter and so does context.

One reason the road toll is increasing is simply that there

are so many more of us on the roads. We added another million people to the

national population in just 2.5 years. The only way for the road toll to fall

in those circumstances would be to envisage that not one single additional

person will fall victim to a road fatality. Mathematically hugely improbable.

For context, a look at road fatalities per hundred thousand

people tells a different story. Here, our rate of road fatalities has been

falling consistently since 1970. Those fondly recalled family photos of kids

piled into the family wagon with no seatbelts were also a deadly time on our

roads. Drink driving in particular, but other aspects of road safety –

including road design – were not conducive to surviving the drive.

Our current rate of road fatalities is around 4.8 per

hundred thousand – a rate which has more or less not changed in a decade.

Source: The Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities

How does this compare internationally? We are less than half

the rate of road deaths in the USA, we are lower than New Zealand, roughly the

same as Canada but higher than countries like Germany or Japan. Interestingly,

Germany offers very high-speed road travel on much of its federal motorway network

the autobahn. Parts of it have no speed limit at all. Clearly the

quality of their highways is a major factor – speed alone is not.

Source: Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional

Development, Communication and the Arts. (2025, October 30). International

comparisons. National Road Safety Data Hub.

How do we compare across Australia? The Northern Territory is statistically the worst of the states or territories, while the ACT is the best. Is the quality of roads in the ACT a factor? Queensland is higher than both NSW and Victoria but is also a more decentralised state.

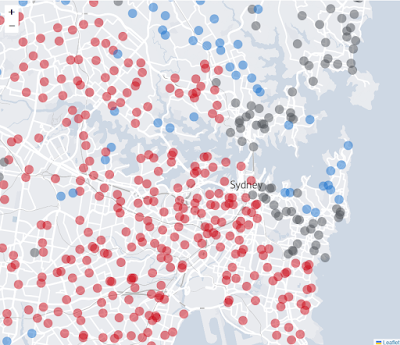

Remoteness is a factor, with remote areas recording many more more fatalities per hundred thousand than major cities. In major cities, the fatality rate is half the national average.

None of this is any consolation for people who have lost loved ones in avoidable road accidents. But it helps shed some light on how we might further mitigate accidents and fatalities.

Arguably, Australia as a whole compares favourably on an international basis. It’s also true that major cities – where the road network is more evolved and where traffic is more congested – is a very different proposition to regional and remote areas where road quality is nothing like the big cities, and where distances travelled are much greater.

If we were serious about reducing the road toll further, we

are entitled to suggest that a focus on better road quality - and driver

behaviour - in regional and remote areas will yield more results than a pernicious

focus on minor transgressions in the big cities.

We are not getting worse as drivers nor are we taking more risks on the roads, which the simplistic focus on overall fatality numbers (rather than the rate per hundred thousand) tries to suggest.

POSTSCRIPT:

The rate of suicides per hundred thousand people is around 11.8 - or more than double the rate of road fatalities (4.8). Males at 18.3 per hundred thousand are almost three times more likely than females (5.5) to commit suicide, and indigenous people (at nearly 34 per hundred thousand) have a record we should be ashamed of. And like road deaths, the rate of death by suicide is much higher in regional and remote areas than major cities.

Suicide was the 16th most common cause of death in 2024 -with 3,307 total deaths (behind variuous cancers, heart disease and other health problems). That is 2.5 times as many died on our roads (1300 in 2024). If saving lives was the objective, would it make sense to invest more effort in things like suicide prevention?