“Tiny houses” are variously defined, but Wikipedia offers a useful

description: “The tiny-house movement is an architectural and social

movement that advocates for downsizing living spaces, simplifying, and

essentially "living with less." According to the 2018 International

Residential Code, Appendix Q Tiny Houses, a tiny house is a "dwelling unit

with a maximum of 37 square metres (400 sq ft) of floor area, excluding

lofts." The term "tiny house" is sometimes used interchangeably

with "micro-house". While tiny housing primarily represents cheap,

simple living, the movement also sells itself as a potential eco-friendly

solution to the existing housing industry, as well as a feasible transitional

option for individuals experiencing a lack of shelter.”

Think Gypsy wagons. Alluring as the description is, the tiny

house promise of being eco-friendly and low cost ignores one very inconvenient truth:

the land on which it sits and the services provided to that land – if they meet

the bewildering array of standards and regulations – are anything but low cost

(or even eco-friendly).

This was dramatically highlighted by some recent research

from the engineering team at Colliers (who acquired Peak Urban). According to their

research, which is based on cost estimates for around 6,800 lots and 3,400 in

construction, across seven regions in South East Queensland, the civil

construction cost per lot is now $157,833. This is 37% more than their

2021 estimate.

Remember, this is just the civil infrastructure cost. It

does not include the raw land cost – it is just the cost of providing services

to that piece of land – water, sewerage, roads etc. Those services need to meet

increasingly higher standards which, combined with today’s market realities,

are driving the cost surge. According to the Colliers Report:

“Increases in civil construction costs due to supply

constraints are the most obvious reasons for increased overall costs. However,

skilled labour shortages have meant that some businesses are paying overs to get

people (if they can get them), but it also means that it is taking longer to

get things done. Authorities are suffering the same, with some being forced to

contract works to external parties which further diminishes industries capacity

to keep up. It’s a perfect storm that is leading to higher input costs across

the board.”

Ironically, some of the drivers of these costs relate to

standards which aren’t always the most eco-friendly or cost friendly. Arguments

against “out of sequence” land development, for example, usually revolve around

the roll out of trunk infrastructure (things like water and sewer mains, or

roads for example). The argument being that the trunk infrastructure must be

supplied in a sequential manner for cost reasons. Yet large scale off-grid infrastructure

options – water collection or waste water treatment for example – which can provide

environmentally superior and lower cost solutions, are often prohibited by

regulation. You are not allowed, for example, to use collected rain water for

anything but flushing your toilet or watering your garden. We have standards! And

your wastewater must be pumped many kilometres through expensive concrete sewer

pumps and energy hungry pump stations to reach a waste water treatment plant,

even though large scale localised treatment options are technically available and

environmentally superior. Once again, we have standards! Using recycled

materials for road surfaces? Standards again.

So back to our tiny house. The cost of bringing services to

the land on which it sits is now around $150,000. The land is also subject to a

per-lot infrastructure charge, and the developer who has generated the lots has

been subject to a range of taxes from land taxes to stamp duties to application

fees and other regulatory and compliance costs. Plus there’s the actual cost of

the raw land. You can see how the physical cost of a block of land – even one

as small as 400 square metres – is now starting at around $250,000 or $300,000 –

and that’s at the lower end (depending on location).

Then you get the pleasure of adding the house, which is also

subject to a range of compliance costs and taxes – including the GST. According

to the Housing

Industry Association (2023):

“In 2019, the Centre for International Economics (CIE)

released a research report Taxation on the Housing Sector which identified the

costs associated with bringing land and housing to market and provided a

breakdown of these costs as either resource costs, regulatory costs (red tape),

statutory taxes (federal, state and local) or excessive charges. The research

showed that the combined costs of the statutory taxes, regulatory costs and

excessive charges equate to 50 per cent of the cost of a new house and land

package. The situation since 2019 has only worsened.”

Many years (2007), when I prepared a report “Boulevard of

Broken Dreams – the Future of Housing Affordability in Australia” for the

PCA – that cost was around a third. It’s now half. No wonder things are getting

worse. (If you want a copy, I can email you one just let me know).

Even more concerning is the equity argument. Buyers of an

entry level new house and land package on the urban fringe – our archetypal

young family of first home buyers – will pay a great deal more in embedded taxes

and charges on their new home than someone buying a multi-million dollar established

home in, for example, the privileged inner-city market of New Farm (or Balmain

for a Sydney equivalent). Our young buyers are buying into an area where the

infrastructure is largely still a promise of things to come. Our New Farm

buyers are buying into a market where other taxpayers have generously funded

the extensive hard and social infrastructure which has made the suburb so desirable,

but they pay no infrastructure levy, no GST, and no other regulatory or compliance

costs. They may grumble about stamp duty but it is far less than the combined

tax bill faced by our young family.

So, the solution to this mess of regulation and tax, which

has made new land for housing a complex and costly exercise, is to suggest building

a tiny house of less than 40 square metres on land which costs over $150,000 to

service, let alone the cost of the land itself?

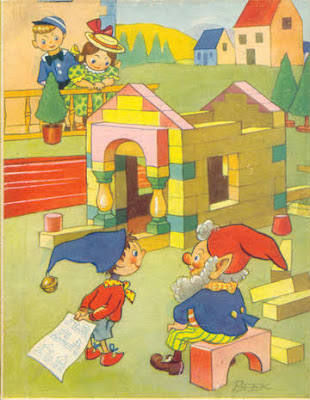

Sorry Noddy and Big Ears, it’s a nice idea, but we’re in the real world now.