We are quick to

celebrate advances in medical science which allow us as a species the

opportunity to live longer. But the consequences of living longer are often

glossed over. The economic consequence is that – worldwide – there are going to

be more and more people in their old age relying on a smaller and smaller

proportion of people of working (and taxpaying) age. It will affect different

nations in different ways, so this is a quick wrap up based on the latest

predictions from the United Nations population division.

The old age dependency ratio is a formula that expresses the

population of people aged 65 and over as a proportion of those aged from 15 to

64. A rising ratio simply means that there are more people aged 65 plus

relative to those aged 15 to 64. There is almost nowhere in the world this is

falling. The world picture shows that we have gone from around 10% in the 1980s

to one in four by 2050. Meaning that there was one person aged 65 plus for

every 10 in 1980 but that this will change to one for every four in 2050. Those

four will have to do the work that ten did in 1980, relative to supporting the

65 plus age group.

The rising dependency ratio is going to affect higher income

nations with more developed economies to a much greater extent than lower

income, less developed nations. The reason is pretty simple: wealthy nations

can afford better health care and higher living standards. The difference is

profound though – by 2050 high income nations will have a dependency ratio

approaching 50%, compared with less than 10% for lower income nations. Will they be able to remain high income nations with this future burden?

The continents that will be most affected broadly align with

income status. The worst affected will be Europe, with a dependency ratio

nudging 50% by 2050. North America is not far behind and Asia will be rapidly

closing the gap.

Amongst the major European nations, Germany has a particularly

nasty problem emerging on the forward radar – a dependency ratio of almost 60%

by 2050. Little wonder German Chancellor Angela Merkel was so keen to attract

such large numbers of refugee migrants (said to be more than 1 million in 2015

alone). France and the UK are following a similar pattern although with

slightly lower dependency ratios and Russia only passes 30% in around 2045.

Closer to home, Japan is facing some serious problems. A forecast

dependency ratio of 70% means there will be seven people aged 65+ for every ten

aged 15 to 64. Japan’s dependency ratio is already problematic and this will

get worse. China is also facing a rapid escalation in its dependency ratio

which will rise quickly from around 2025, effectively almost doubling in the ensuing 25

years. I wrote about China’s people shortage (being a shortage of working age

people) a couple of years back. You can click

here to read it.

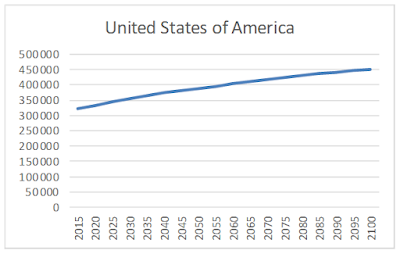

Australia itself shares a great deal in common with the USA

and Canada in terms of our aged dependency ratio. We are currently in the midst

of a significant increase which will see our dependency ratio rise from a

fairly stable band of 15% to 20% from 1980 to 2010, to one in three by 2035.

This will pose a range of budgetary challenges on both the income (tax) and

expenditure (health and welfare) sides going forward.

The good news at least is that while we are increasingly

better informed about the economic challenge of an ageing society, we are not

ageing quite as fast as some places. Maybe we can observe closely how nations

like Germany or Japan handle this escalating dependency challenge, and

essentially copy the policies that seem to work best?

The bigger challenge is that further advances in medical

science and disease prevention will mean these dependency ratios could in

reality be much greater challenges in the future. Living to 100 might be

commonplace for today’s millennials. Their children may expect to live to 120.

But the question of how world economies – which were never designed for this

demographic pattern – are going to afford to support societies where there will

be nearly as many people aged 65 plus as there are of working age, is a big one

and it’s unanswered.

Maybe in the future old age will no longer be an ambition

but something for which we need a cure?