Increasingly, I am curious why the presence of a train station on a map immediately conjures up in the minds of some urban planners images of potentially vast numbers of people transiting by rail – an opportunity too good not to capture. ‘Transit oriented development’ as a concept seems in practice almost entirely fixated on trains as THE mode of public transport to be leveraged. Even if the said station is clearly little used, it’s the potential of that station to one day carry huge numbers of commuters which will help ‘solve’ our congestion problems – at least in the eyes of some starry-eyed dreamers.

While cities with extensive commuter rail networks – many built a hundred years ago or more – are blessed with preexisting infrastructure, it is also true they have grown up for a century around that infrastructure. Cities without it can face economic ruin by trying to introduce it later as an overlay. One look at Melbourne’s disastrous ‘suburban rail loop’ – which if ever completed will be the most expensive project ever in Australia’s history at $300billion to $400billion (from an initial estimate of $50billion) ought to be enough to scare anyone off. In Brisbane, the Cross River Rail – a 10klm underground rail extension with a price tag of nearly $20billion (original promise $5.4billion) – is a reminder closer to home that these are eye wateringly expensive undertakings.

Ironic then that a much lower cost and immensely more popular form of public transport never seems to get as much attention. Would you be surprised to learn that across south east Queensland, buses carry more than double the number of people than trains? In the fourth quarter of 2024-25, the bus network accounted for 31 million trips. Rail accounted for just 14 million – under half. Ferries, while a very enjoyable mode of public transport, provided a paltry 1.9 million trips. Trams – essentially the Gold Coast service – accounted for nearly 3.5 million trips.

Sydney is different. There, rail carries a touch more than buses – with 279 million annual rail trips versus 240 million annual bus trips. Very broadly, that’s close to a 50:50 split. Ignoring buses would discount half of the public transport trips across the region. (The iconic Sydney ferries ferry around 15 million trips annually, while the light rail is around 40 million trips). And in Melbourne, trains rule with 40% of public transport trips, while trams account for 35% and buses a quarter of trips.

Part of the explanation for the mode split in Brisbane is best illustrated by the routes. The rail network across Southeast Queensland is quite limited. It began life as mainly a freight network, and a fledgling one at that. Hence, the cost of retrofitting rail over an urban form that evolved mostly in the era of the convenient and affordable motor car is now prohibitively expensive.

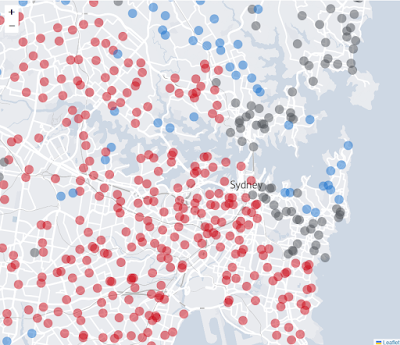

The bus network by comparison looks more like the circulatory system of the human body – with arteries and veins all across the city.

Convenience wins every time. The bus network also caters for suburb-to-suburb trips in a way that trains cannot. Further, the bus routes can be changed as the city evolves, at relatively minor cost because they chiefly use the pre-existing road network. Now enter the Brisbane Metro – Jimmy Rees’ hilarious nomenclature aside. The limited initial Metro network is already proving popular – fast, electric, quiet and turning up every 5 minutes. Future network extension for the Metro is readily possible because it can turn corners and use the road space available (trains can do neither). The Metro has, in my view, a huge future in the region.

So why is it then that we tend to overlook the role of buses or the metro in our region, and continue with a preoccupation with rail? When we do this, we ignore roughly two thirds of the public transport network, in favour of the one third. Where’s the sense in that?

Instead, why aren’t we talking more often about transit-oriented development opportunities that work in with the bus network, bus stations and interchanges? Why not envision a future of electric, autonomous buses shuttling people around the city from suburban hub to suburban hub? And the major interchanges of that network are the future transit oriented centres of activity where development is concentrated with jobs, health care and education all catered for?

Is the train obsession just some legacy fantasy view tinged with images of Euro/UK stations, of puffing steam engines and Harry Potter vibes? I just don’t get it.

Oh and a post-script. The advent of 50c fares for public transport may have been heralded as a ‘congestion busting’ move but the reality is more benign. Our overall public transport use is back to where it was pre-covid, despite the addition of several hundred thousand more people in that time.

The increase for August 2025 compared with the previous year is perceptible, but only just. Keep in mind that the addition of all these public transport modes represents only around 8% of trips in southeast Queensland.

That subsidy now means that 95% of the cost of each and every trip is subsidised by the taxpayer. The 50c doesn’t even cover the costs of running the tap on and off infrastructure. The taxpayer subsidy is currently averaging around $19 per person per one way trip across all modes of public transport. For rail, it’s much higher at around $30 per person per one way trip. For buses it’s much less: around $6.

Another good reason to give buses a lot more attention.